The Hammer and Sickle Journalist: Why Paul Mulholland’s Branding Exposes His Extremist Leanings

Introduction

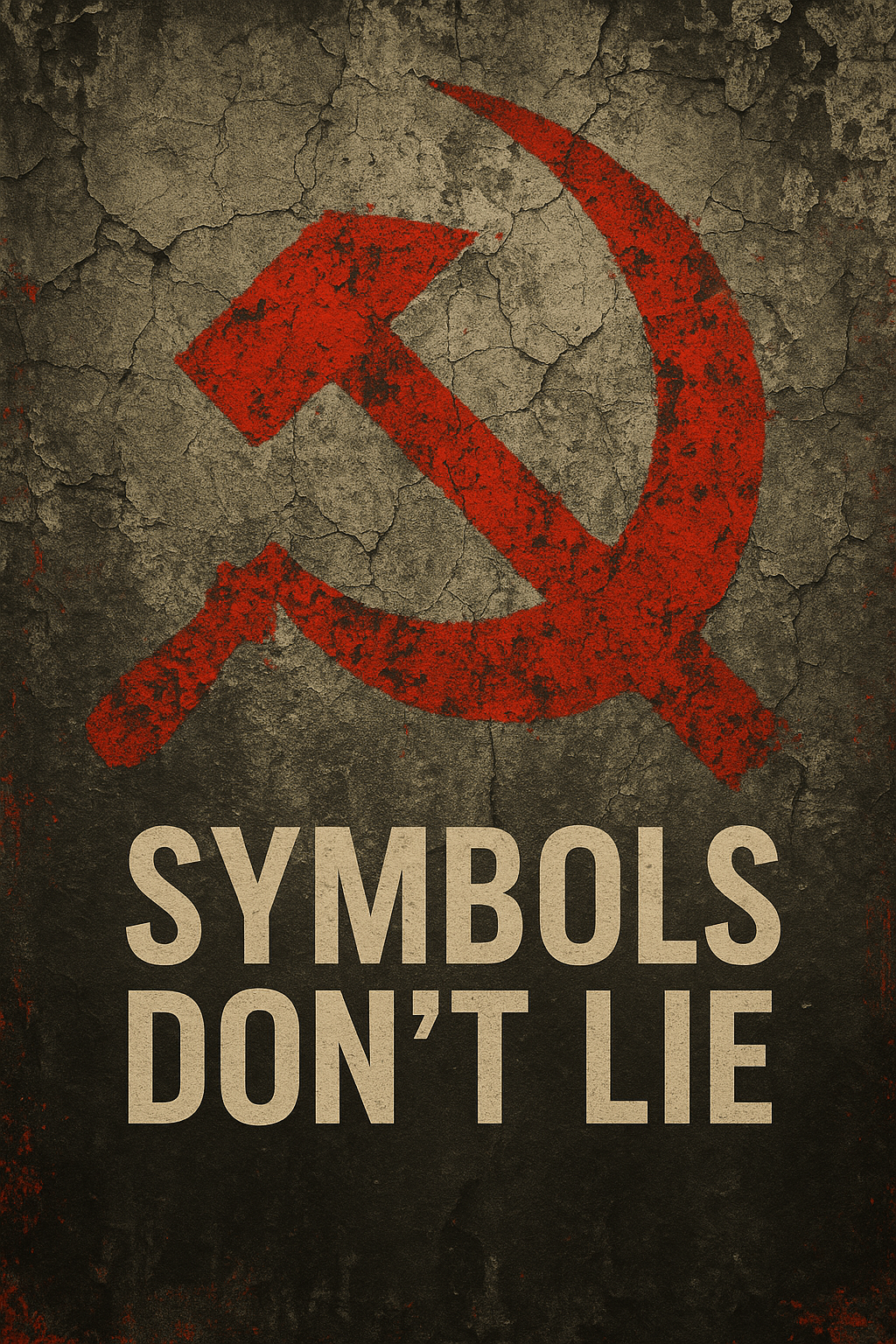

Paul Mulholland walks onto YouTube draped in the hammer and sickle like it’s a press badge instead of a scarlet confession. A journalist, he calls himself. That’s the first false statement on the record. Exhibit A: the logo of gulags, famines, and purges — framed neat and proud on his channel like a neon sign over a dive bar. You don’t need an affidavit to know what that means.

Journalism, by any black-letter definition, demands impartiality and credibility. The duty of care is simple: you seek truth, you don’t fly banners of ideology. But Mulholland plants the red flag in his masthead and dares to call it reporting. It’s not branding, it’s bias. Res ipsa loquitur — the thing speaks for itself.

This isn’t aesthetic. It’s not some edgy undergraduate poster tacked up over a futon. It’s a declaration of allegiance. The hammer and sickle is the swastika’s left-hand cousin: one promises racial supremacy, the other promises class utopia, both delivering mass graves and censored tongues. When you hoist that symbol and wrap yourself in the word “journalist,” you’re not informing the public — you’re confessing to activism under false pretenses.

So here’s the thesis, the indictment: Mulholland’s hammer and sickle is Exhibit B of his bias, and it nukes any claim to journalistic integrity. His brand is not a neutral byline; it’s a red-stained calling card. To let him slide would be malpractice.

The Symbol Itself

The hammer and sickle isn’t a thrift-store graphic or a nostalgic design quirk. It is the registered trademark of one of history’s most repressive machines, stamped across gulags, famine zones, and the silenced mouths of those who believed they had the right to publish freely. It is not abstract. It is not neutral. It is Exhibit C: the emblem of regimes that turned entire continents into prison yards.

Run the numbers like a forensic accountant and the balance sheet is written in blood. Stalin’s engineered famine in Ukraine — the Holodomor — left millions dead, their bodies stacked like cordwood. Mao’s Great Leap Forward propelled tens of millions more into early graves, progress measured in empty rice bowls and swollen stomachs. These are not marginal notes; they are the bill of particulars. When you see that red symbol, you are looking at liability in the millions of human lives, prima facie.

Now, imagine a self-styled journalist broadcasting with a swastika in the corner, or a Confederate battle flag as their backdrop. Every viewer would immediately understand the bias on display, loud enough to disqualify any claim to impartiality. The hammer and sickle carries the same evidentiary weight — arguably heavier, because it cloaks itself in the language of “worker solidarity” while shoveling dirt over mass graves.

Authoritarian regimes never only weaponized tanks; they weaponized truth. Pravda in the Soviet Union was not journalism, but propaganda under state lease — a daily reminder that speech had been repossessed by the Party. The same template was repeated in Mao’s China, Castro’s Cuba, and Pol Pot’s Cambodia: press licenses stapled to ideology, journalists reduced to stenographers of the regime. Caveat lector — reader beware — the hammer and sickle does not signal information; it signals indoctrination.

Mulholland hangs that emblem over his channel and still calls himself a journalist. That is not branding; it is a declaration of partiality. A flag is never “just cloth,” and this one is not a harmless aesthetic choice. It is evidence. It is bias forged in iron. It is the red-stained proof that what he offers is not journalism at all, but activism in costume.

Why It Matters — and the Double Standard

Defenders will shrug and say it’s “just a symbol,” a historical flourish, nothing more. That argument collapses on first inspection. Symbols are not ornamental; they are declarations. They anchor brands, shape identities, and tell an audience who you are before you say a word. Mulholland has chosen to brand himself not as a journalist in pursuit of impartial truth, but as the hammer-and-sickle journalist. His logo is his opening statement. His set design is his affidavit.

To let that pass unchallenged is to normalize propaganda dressed as reporting. Journalism, properly understood, is supposed to be the public’s defense against narrative capture. But Mulholland’s channel does the opposite: it models bias as virtue, broadcasting under a banner inseparable from state repression. The danger is not theoretical. An audience unfamiliar with the symbol’s baggage, or hungry for contrarian takes, may mistake his commentary for investigative work. The result is confusion, disorientation, and another notch in the erosion of public trust in journalism.

And then comes the hypocrisy. Mulholland and his defenders rail against “corporate media bias,” decrying mainstream outlets as compromised and agenda-driven. Yet his own bias is not hidden in tone or word choice; it is literally nailed to the wall in red and gold. If media conglomerates are guilty of conflicts of interest, then his project is guilty a fortiori — his allegiance is declared in symbols that carry more baggage than any advertiser ever could.

Now imagine the mirror image. Picture a journalist waving an alt-right flag in their banner, or displaying a fascist emblem above their desk. The reaction would be immediate and merciless: outrage, condemnation, expulsion from any claim to journalistic legitimacy. And that response would be correct, because symbols of extremism compromise credibility the moment they appear.

So why does the hammer and sickle get a pass? Why is one brand of authoritarian iconography met with outrage, while another is indulged, even romanticized, under the guise of “workers’ history”? This is the cultural blind spot: far-left extremism slips through filters that catch far-right extremism instantly. But authoritarianism doesn’t change its nature depending on the color of its flag. Repression is repression. Mass graves are not absolved by the rhetoric printed in the Party manifestos that dug them.

As critics of communist apologetics have long pointed out, brutality doesn’t stop being dangerous simply because it cloaks itself in the aesthetics of solidarity and equality. Authoritarianism by any other name still silences speech, still crushes dissent, still uses media not to inform but to indoctrinate. The hammer and sickle is no less toxic than the swastika or the fasces. To pretend otherwise is not nuance; it is negligence.

Mulholland’s branding is not an oversight, and it is not harmless. It matters because it reveals his hand: activist first, journalist second — if at all. And it matters because we, the public, are asked to normalize what should be rejected outright. To accept that symbol in journalism is to erode the very foundations of credibility in reporting. Res judicata: the matter is settled.

Activism in Disguise

At the end of the day, journalism is defined not by who holds the microphone, but by the standards under which it is held. Independence, impartiality, verification — these are the tests. Mulholland fails each one the moment he pins the hammer and sickle to his brand. That symbol is not an accessory; it is an affidavit of bias. It tells us that his allegiance is already sworn, his verdict already written. He is not in the business of informing the public. He is in the business of persuading them.

That makes him an activist — and activists have their place, but they do not wear the title of journalist without cheapening it. By flying that banner, Mulholland does more than confess his partiality; he de-legitimizes the very profession he claims to represent. Every time he invokes “journalism” while cloaked in the hammer and sickle, he erodes the line between reporting and propaganda. And once that line is blurred, the damage does not stop with him. It spreads to the wider institution, fueling public cynicism and distrust.

The press is already on trial in the court of public opinion. To allow figures like Mulholland to masquerade as journalists while openly displaying extremist iconography is to hand the jury more evidence for the conviction that journalism is dead. But journalism is not dead — it is only endangered. And it is endangered precisely because its title has been hijacked by partisans who wish to launder activism through the credibility of reporting.

Mulholland is free to wave whatever flag he likes. That is his right. But he is not free to do so and claim the protections, prestige, and authority of a journalist. The hammer and sickle on his channel is the dispositive proof: he is not reporting from the neutral ground of inquiry. He is campaigning under a partisan banner. In the simplest terms: he is not a journalist. He is an activist in disguise. And every time he invokes the word “journalism,” he dilutes it further, until the title itself risks becoming meaningless.